The latest publication from the Energy Transitions Commission (ETC): "NDCs, NCQG, and Financing the Transition"

LONDON, Oct. 24, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- "Climate finance" will be a key subject at COP29, with debate in particular on the proposed "New Collective Quantified Goal" (NCQG) for financial flows from high-income to low-income countries. But the term "climate finance" is often used vaguely and broadly, covering several different challenges and priorities.

The Energy Transitions Commission's (ETC) latest publication "NDCs, NCQG, and Financing the Transition" therefore clarifies the nature and scale of different types of finance required, and proposes four principles to ensure a useful conclusion of the NCQG debate. It also explains the vital role that updated National Determined Contributions (NDCs) can and must play in unleashing financial flows.

The NCQG and NDCs

The Paris climate pact included a commitment to agree on the extent to which higher-income countries will financially assist low-income countries with mitigation and adaptation. This NCQG will replace the current $100 billion per annum target for climate finance flows from developed to developing countries which was agreed in 2009 but consistently undelivered until 2022.

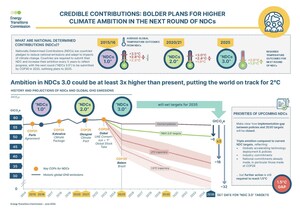

The NDCs are the crucial mechanism, established by the Paris Conference, through which countries commit to voluntary national actions to reduce emissions, in line with the global objective of limiting global warming to well below 2°C. Countries are required to submit ratcheted NDCs every five years.

Current NDCs (submitted in 2020) put the world on track to overshoot 2°C warming by 2050 even if implemented. Increasing ambition in the next round of NDC is therefore crucial but achievable because dramatic cost reductions in key technologies (in particular solar PV, wind power and batteries) mean that countries can now rapidly reduce emissions while continuing to meet growing demands for affordable energy access and use.

"COP29 debates on the NCQG need to start with a clear definition of the very different categories of "climate finance" and recognition of the different appropriate funding sources. And however the NCQG debates conclude, countries should use updated and more ambitious NDCs to help unleash the private finance which will play the primary role in funding capital investment for mitigation. But it is also essential for development banks to play an increased and more effective role in supporting financial flows to middle and low-income countries." - Adair Turner, Chair, Energy Transitions Commission.

"Through frameworks like the NCQG and NDCs, countries can set ambitious goals backed by policies that attract large-scale investments from the private sector and can meet the majority of finance needs for climate mitigation and adaptation. Multilateral Development Banks are crucial to providing affordable finance for decarbonising energy systems and building climate resilience in developing nations while ensuring that economic growth aligns with the clean energy transition." – Nicholas Stern, Chair, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change.

"Climate finance" – the need for clarity on categories, quantities, and potential sources

The term "climate finance" is often used without distinguishing the types of finance required which are financed in quite different ways. The ETC's brief draws a clear distinction between:

- The capital investments needed to establish zero carbon energy systems globally and mitigate climate change. These investments average around $3 trillion annually until 2050.1 Most of this investment will be financed by private institutions delivering an attractive rate of return to investors if appropriate real economy policies are in place. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and other public financial institutions must also play a significant role to support financial flows to middle and low-income countries.

- Concessional or grant payments may be required to mitigate emissions in specific areas – in particular, to close coal plants early, end deforestation, and finance carbon removals – which may not generate a return on investment. These payments could come from carbon offset markets, philanthropic funds, or inter-governmental contributions. The ETC estimated $300 billion of this type of payment is required annually, but actual flows are unlikely to reach this magnitude, necessitating other measures, such as strong policy, to achieve emission reductions.

- Investments in adaptation – for instance in flood management or coastal protection – to deal with the already inevitable consequences of global warming. The Songwe-Stern 2022 report suggested these might reach $250 billion per annum in middle and low-income countries. A significant part will be financed from domestic resources (especially in middle-income countries) but there is a major essential role for loans provided by MDBs and for concessional payments or grants from high-income countries.

- Payments to help lower-income countries cope with the loss and damage already produced by climate change. The Songwe-Stern report estimated that these costs in middle and low-income countries might reach $200-$400 billion per annum by 2030. At COP27 in 2022, the principle was agreed that higher-income countries should contribute towards meeting these costs.

Optimal results from the NCQG debate at COP29

There are widely divergent views on what the NCQG should cover. Some countries believe that "loss and damage" payments should be included, but others argue that the focus should be on mitigation and adaptation finance. India and some Arab countries have called for a headline figure of over $1 trillion per annum but high-income countries have not yet committed to any figure above $100 billion per annum. Many of those high-income countries believe moreover, that the definition of contributing countries should be expanded to include high per capita emissions countries such as Saudi Arabia, UAE and China.

Given this divergence of opinions going into COP29, there is a risk that no consensus will be reached or that the resulting agreement will use vague language that can be interpreted in many different ways.

The ETC's focus and expertise relate to the challenge of mitigation and we believe that the NCQG will have the best impact on global mitigation efforts if it includes:

- Clarity on the different types of investment/payment needed, sources that can meet this need (e.g., private finance, MDB loans, or concessional/grant finance), and what is covered by the NCQG headline figure.

- Strong focus on the very large-scale financial flows required to support mitigation in middle and low-income countries (e.g., about $900 billion a year) and the significant role that MDBs must play, including in catalysing private financial flows. Multiple reports have already described what must be done to enable MDBs to play a greater and more effective role.2 Analysis should now be replaced by action.

- Expansion of the definition of contributing countries to include at least China and high-income oil and gas producers such as Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Qatar because of these countries' high per capita emissions and low cost of capital.

- Strong support for new sources of funds such as:

- Global carbon taxes on aviation and shipping as proposed by the Nairobi Declaration.

- The allocation of revenues from border carbon adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs) to support climate finance flows to low-income countries.

Key priorities for the NDCs

Most capital investment to drive mitigation will be financed by private institutions (or state-owned companies acting in a market-competitive fashion). But governments have a responsibility to incentivise that investment through well-designed policies. Clearer and more ambitious NDCs could also help by providing certainty about future objectives and supporting policy. The ETC recommends that the next round of NDCs should:

- Set more ambitious emission reduction targets to reflect technological progress and cost reductions already made, and align NDC objectives with existing policy commitments.

- Define strong links between targets and supporting policy, acting as comprehensive roadmaps for implementation.

- Contain absolute or equivalent emissions targets for specific sectors and cover all greenhouse gases.

- Identify the investments required to deliver emissions reductions and the broad balance of financing sources envisaged.

Download the briefing note: https://www.energy-transitions.org/publications/ndcs-and-financing-the-transition/

Notes to Editors

1 In our 2023 report Financing the Transition, the ETC estimated that $3.5 trillion per annum is required for climate mitigation investment between now and 2050. This will be offset by an average annual reduction of $0.5 trillion in fossil fuel investment, to give a net figure of $3 trillion per annum.

2 For example, Independent Expert Group (2019), Transforming the Financial System for People and Planet; Blended Finance Taskforce (2021), Better Finance, Better World; European Investment Bank (2022), Joint Report on Multilateral Development Banks' Climate Finance; OECD (2022), Multilateral Development Finance 2022; International Finance Corporation (2023), Mobilisation of Private Finance by Multilateral Development Banks and Development Finance Institutions.

NDCs, NCQG, and Financing the Transition: Unlocking Flows for a Net-Zero Future builds on previous ETC work including, Financing the Transition and Credible Contributions. It is based on analysis developed in extensive consultation with ETC Members from across industry, financial institutions, and environmental advocacy and constitutes a collective view of the Energy Transitions Commission. However, it should not be taken as members agreeing with every finding or recommendation.

The ETC is a global coalition of leaders from across the energy landscape committed to achieving net-zero emissions by mid-century. For further information on the ETC please visit: https://www.energy-transitions.org

Logo - https://mma.prnewswire.com/media/1935158/Energy_Transitions_Commission_Logo.jpg

Share this article